Admittedly half-drunk, in a cold night of the winter of 2018, I found myself at dinner with friends defending the notion that a new world war was on the horizon.

War as a necessity

To the sober me, the signs felt unmistakable. Globalisation was essentially a fiefdom system. Western corporations (the ‘Lords’) exploited China and later on South and South-East Asia (the ‘Serfs’), which provided cheap labour and raw materials. The rules of engagement were not democratic, and those countries had very limited agency. Yet, although global supply chains, controlled by large corporations, sought to keep wealth concentrated at the top, the previous lives of the serfs were so miserable that even a small improvement ignited a thirst for more, much more. It compelled them, until en masse they reached the bottom of the fortress walls and demanded entry.

In ancient times, such revolts culminated in heads rolling, predominantly those of rebelling serfs. Nowadays, however, there are simply too many heads.

The long term inconsistencies introduced by globalisation are quite natural, when you consider it, and most global corporations probably intuited that eventually they would have to pay the price. However, that realization didn’t concern the CEOs, who just cared about short term shareholder value and their multi-million exit packages. They knew they would be gone long before the revolt: according to a recent study, the median tenure among S&P 500 CEOs has decreased by 20% over the past decade. The Lords left with the honors and the wallet.

Eventually, I believed that this system would have generated so much friction (as the serfs – not only in China, but also in India and elsewhere – claimed their place in the command room) that the inevitable result would be a global war.

In his “Philosophy of Right” (paragraph 324), Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel characterises the war as an occasional necessity to remind people about the universal.

War has the higher significance that by its agency […] the ethical health of peoples is preserved in their indifference to the stabilisation of finite institutions; just as the blowing of the winds preserves the sea from the foulness which would be the result of a prolonged calm, so also corruption in nations would be the product of prolonged, let alone 'perpetual', peace.

As nation-states began reclaiming the power they had ceded to global corporations—especially through increasingly interventionist commercial and industrial policies—my case for a global war grew even stronger.

But in the last few weeks, I changed my mind.

A different view

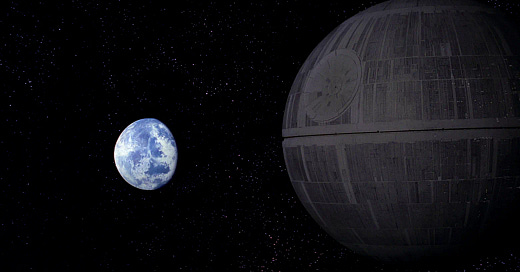

War – a war for global control, that is – has an annoying characteristic: we would all die, even those who waged it. Isn’t there something else?

Much noise surrounds the abrupt shift global politics took with the election of Donald J. Trump, but it certainly seems a new wind is blowing. There is a suggestion of a different way to interpret political power, alliances, historical rivalries, and the dynamic between nations. It’s too early to determine if this attempt will be hindered by the shifting sands of bureaucracy, leading everything to settle once more. However, the swing is so drastic that it warrants attention.

And although it manifests through harsh or even vulgar rhetoric, I do not perceive this shift as drawing us closer to war as a means to alleviate accumulated domestic and international tensions. It leads to something else: the return of a global order based on rivaling empires of exploitation.

To me, one of the strongest arguments for a global war was what I saw as the inevitable growth of a multipolar world. It’s peculiar that this multipolarity is gaining traction now – this year’s Munich Security Report is titled ‘Multipolarization’, a term so unappealing that you might wish the English language were not so adaptable – when it is, in fact, coming to an end, or rather, being drastically reframed.

The multipolarity emerging until a few months ago was, in fact, a combination of a weakening bipolarity (US-China) and the rise of about ten ‘Middle Powers’. These countries do not ‘swing’, as, in my opinion, Goldman Sachs misrepresents them. Rather, they multi-align. They do not pledge allegiance to one power or the other - to China or the US – but get from those two what they need to thrive. They are (were) permitted to do so because the US and China are desperately trying to win them over. Consider India, embracing the West politically while purchasing all the Russian oil that we no longer buy; or Mexico, assisting China to circumvent US sanctions. Or Brazil, South Africa, even the European Union… there are so many examples.

If the new wails of the US administration’s turns into a structured doctrine, then multi-alignment is over. Look at Panama, which was forced to abandon its commitment to China’s One Belt One Road within just two days. Then there’s Mexico and Canada, who presented themselves in repentance to suspend the punishment that the US had waged on them … Soon, it will be India’s turn. The United States is no longer willing to indulge the little games of middle powers, and it is ensuring they understand that.

Considering the global consequences of this change, it seems to me that the US is presenting its rivals—China primarily, but also India and Saudi Arabia—with a new game: let’s play Empires.

As has historically been the case, these empires will be built upon and managed through economic advantages (AI for the US and China, energy for Saudi Arabia, and a young, surging population for India). They are unlikely to be empires of incorporation but rather of expropriation, with the difference between the two brilliantly explained by Prof Bhambra in this lecture:

First, colonised populations being subject to rule but not part of a common order of rule. Second, legitimation of colonisation on the basis of some idea of civilizational difference and hierarchy, including that of scientific racism. Third, the extraction of resources (material resources, taxation, and human beings themselves) from the colonies for the primary advantage of those in the metropole. These three aspects constitute empires of extraction as fundamentally distinct from empires of incorporation.

And finally, their growth is likely to face little opposition; the advantage of these four countries is so overwhelming that, as they transition from collaboration to empire formation, few would be able to resist them. No war, then, for now. But plenty of social and economic exploitation, even abuse, to glorify the splendor of their Lords.

Curtain call

A final note. You may have noticed the absence of Europe from my list of empires. Unfortunately, it’s not an oversight. Despite its still substantial economic market and somewhat impressive record with imperialism, it seems to me that Europe will sit this one out. If empires of expropriation are sustained by a group of vassal countries orbiting around the Lords, then it is unclear where Europe should be looking to find its own. It had a chance with Africa, conveniently located to its south, but it squandered it long ago. And where is its crushing economic advantage?

It’s unlikely that J.D. Vance will ever be sent to China, to India, or to Saudi Arabia to speak to these countries’ leaders in the same manner he did during the Munich Security Conference. For he was not assaulting Europe or severing the historical ties of friendship, as many aggrieved commentators remarked. Rather, he was seducing it, enticing it, making the case for its leaders to join the new US empire. As serfs, of course, but – hey – such are the times.

You were not kidding when you said this post was going to be chilling... I tend to agree with most of it. A a simple-minded American, I cannot quote Hegel, but I give myself a simple explanation of what is going on. The geopolitical world has always been a rather nasty and dangerous place. For a brief spell following the fall of the Berlin wall, US power was so overwhelming that peace seemed assured, aside for some local conflict and assorted terrorism of course. Then it became increasingly clear that countries will act in brutal and selfish ways whenever they have the chance. The US is signaling to the rest of the world that if you want to play by these rules, it's fine by us (though we don't particularly like it). Europe insists on seeing the world as it wishes it were, an attitude that looks increasingly infantile. Lastly, I personally don't think Vance was enticing Europeans to join the American empire as serfs. I think he was just telling them that it's not the US that is abandoning Europe, it is Europe that abandoned the US and the values we used to share. Thanks for another thought-provoking post.

An "Empire" - so called in the strictest sense of the word - cannot change his geopolitical approach to the destinies of a people in two months !!