Let me step away from economics and geopolitics for a moment—though everything is interconnected in some way.

I’m currently watching Station Eleven, the 2021 TV series adapted from the novel of the same name by Canadian author Emily St. John Mandel. Plot summaries are easy to find. In short, it revolves around the rebirth of communities after a catastrophic pandemic wipes out life as we know it. Beyond being a beautiful work, visually stunning and one of the few examples of non-linear narration that actually works without feeling like an unnecessary show of skill, it sparked in me some fundamental reflections on society that I’d like to share.

COVID-19 and the promise to be better

First, COVID-19. Emily St. John Mandel's novel Station Eleven was published in 2014, six years before the real pandemic that brought life in our cities and beyond to a standstill. In an ironic twist, filming for the TV adaptation began in February 2020 but had to be halted due to the onset of COVID-19. The pandemic (the real one) turned out to be a little more than a sneeze—taking its decent toll, surely, but nowhere near what the visuals of our deserted cities would have suggested.

During lockdown, we relearnt how to communicate with one another as we were forced to stay apart. I remember video calls with friends and family often turned to the hope that society would emerge from the crisis transformed—more compassionate, unified, and appreciative of human connection. Somehow, we hoped, that spiky virus had taught us a fundamental lesson, a warning, ‘un avertissement sans frais’ as the French expression so effectively put it: that our need for one another is fundamental, more than anything else.

As it happened, arguably, we got out of it worse. This naive reverie was debunked immediately as the lockdown was lifted: huge lines of still-distanced crowds outside of luxury shops in our cities. As we were allowed back into society, we swiftly returned to consumerism instead of the deeper social connections many anticipated. It turned out we video-called our distant cousin because we could not Zoom with a Gucci bag – yet.

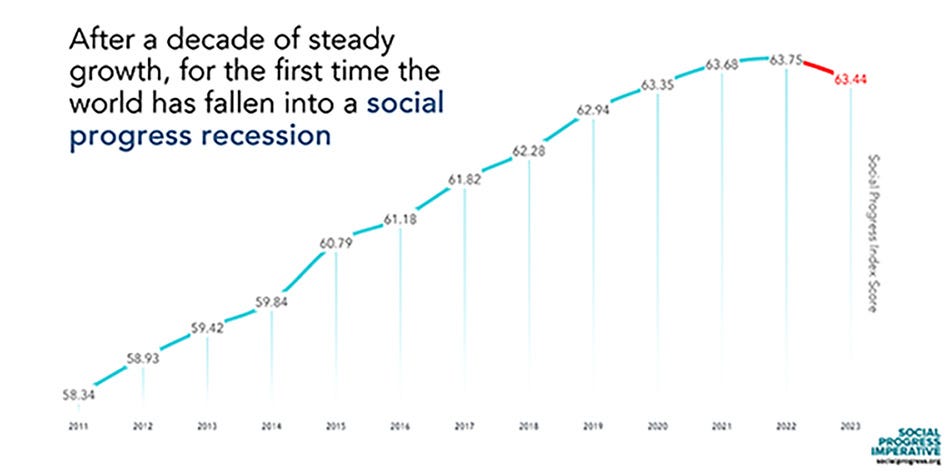

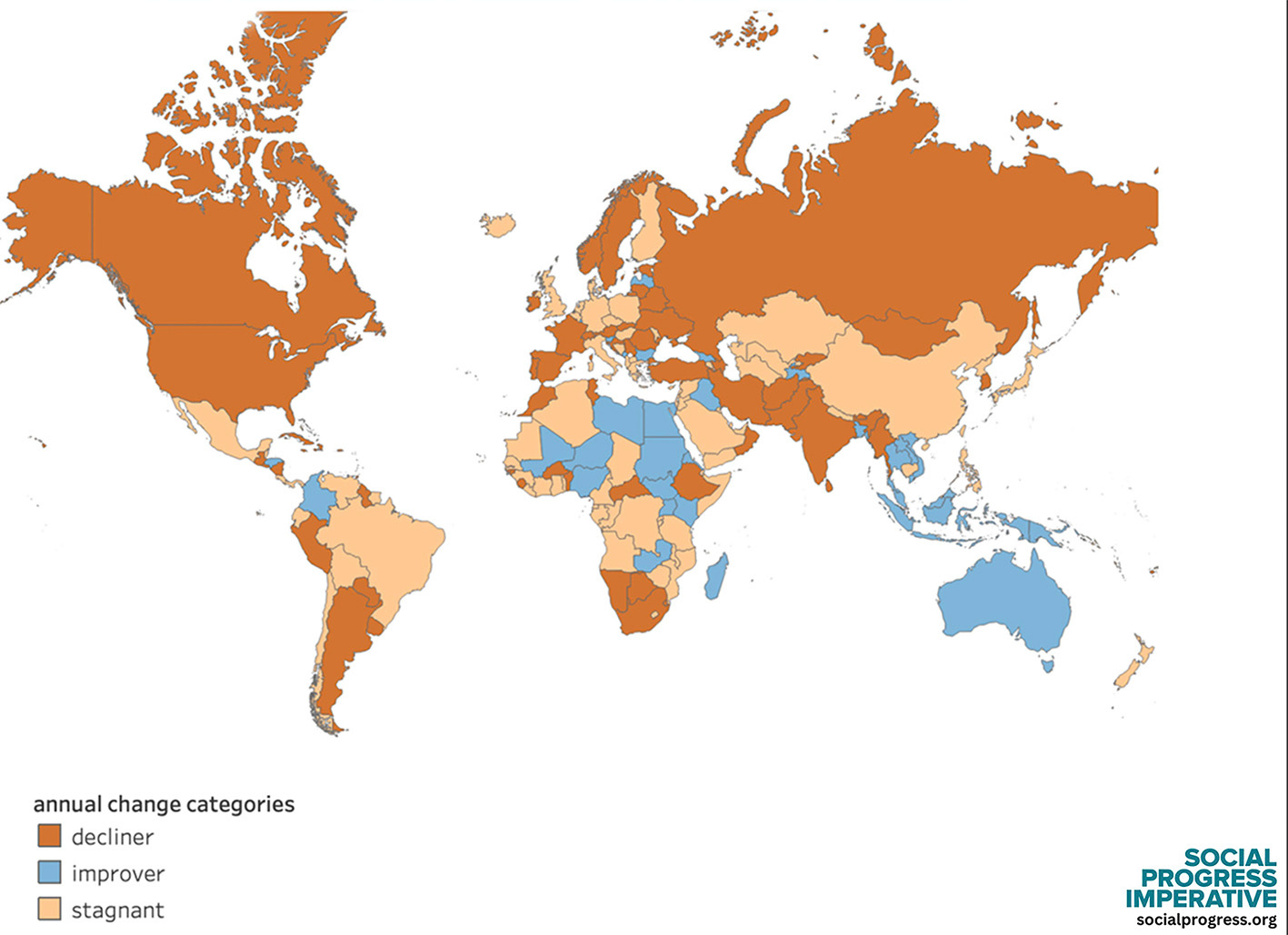

The Social Progress Imperative, a nonprofit organisation based in Washington D.C., publishes the Social Progress Index, which tracks the social performance of 170 countries using 52 indicators. Recent findings indicate that, for the first time since the index's inception, global social progress has declined in 2023. Significant decreases were observed in wealthier nations – us. The few areas of improvement are North Africa and South-East Asia, likely due to their previously lower baseline scores.

So, no, COVID-19 did not make society fairer or more equal—if anything, it had the opposite effect.

Would a more severe pandemic have led to a more profound social transformation? I doubt it—and, in any case, I have no desire to find out through such a harsh trial.

So, what way forward?

The Social Media debacle 2.0?

Once again we are promised that change for good is coming as a by-product of a major technological shift. AI is loaded with so many great expectations in any possible field—productivity, new jobs, creativity, surplus of time. It is often linked to social improvement (see here and here). Lots of wishful thinking, for the moment, as with productivity, new jobs, and creativity. As for the surplus of time, AI is transforming tasks that once took days into mere seconds but how are we utilizing this newfound time?

What is very real, for now, is how much it is already costing. In 2024, major technology companies collectively invested approximately $200 billion in this sector, with projections indicating even higher expenditures in 2025. Another certainty is that AI is going to fiercely compete with human beings for energy use. The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects that data centers' energy consumption could double by 2026, driven in part by the demands of AI and cryptocurrency technologies. As my friend Marco Annunziata wrote in his recent blog, these estimates might be conservative.

The promises of social improvement through technological progress remind me of the inception of social media platforms. This technology was introduced as a driver of social progress. The potential for communities was no longer limited by space or physical proximity but became global. We could make friends anywhere, and society was expected to become more inclusive and participatory. I am sure these and other utopian ideals were used to pitch to venture capitalists.

Even then, these promises felt hollow to me. At a time when humanity was becoming more disconnected, tech entrepreneurs provided people with the perfect tool to amplify the self. The notion that giving a universal voice to people increasingly focused on themselves would lead to social progress was, and still is, as absurd as expecting a hater with a megaphone to suddenly shout harmony. Reading The Ethics of Authenticity by Charles Taylor clarifies why social media could only become a force that undermines society. As Siva Vaidhyanathan writes in his book Anti-Social Media: How Facebook Disconnects Us and Undermines Democracy:

“Social media, and Facebook in particular, do not foster conversation. They favor declaration. They do not allow for deep deliberation. They spark shallow reaction.”

Is there no hope, then?

A new focus on compassion

Station Eleven suggests there is: re-booting communities by axing them on art and humanities. In both the novel and the series, one of the social nuclei formed by survivors is held together by artistic expression. The Traveling Symphony Station performs Shakespeare plays, has a graphic novel as its Constitution, and carries the motto ‘Survival is insufficient’, a direct quote from Star Trek: Voyager. The underlying message is that everything we need to rebuild communities already exists; it’s just buried beneath layers of anti-social ideas and relentless exhaltations of the self. The key to rediscovering our social roots is rediscovering beauty, artistic creation, and how a word, a verse, a brushstroke, or a melody reminds us of our connection, solidarity, and compassion.

In fact, the message isn’t as simplistic as “art saves society.” Rather, survival, thriving, and the artistic creation are inseparable; they are one and the same. Like social media, art also is declarative. But there is still a conversation—albeit a silent one, a dialogue between souls. Declarations in art remain profoundly human: they do not impose, they share. Sometimes they console, like Bellini’s Madonnas; at other times, they tear you apart, like Guernica; or the Hamlet monologue on grief that Kirsten – the main protagonist of Station Eleven—recites as she splits into a younger self, an eight-year-old child who, in the throes of a devastating pandemic discovers chillingly that her parents are dead. Art projects emotions rather than ideas, and in doing so, it triggers and nurtures compassion (from the Latin cum-passio: sharing passions), our most human feeling.

Maybe it is simplistic, even naive, to believe that in our times of hate and self-absorption communities could be rebuilt around art. But if we never try, we’ll never know.

We are not—trying. More than that: we are actively working to sever the link between art and the human being. The new frontier is GenAI creating art, with billions being invested to reach this milestone. We will watch in awe as GenAI, no longer limited to mimicking the works of the Masters, sets its own stylistic standards—where the original human contribution becomes so diluted that it is rendered indifferent and powerless.

But hey, at least when pandemic strikes again, we will still have DALL-E. The only consolation might be that, like the most deadly viruses, GenAI could fall victim to its own success and perish alongside the last of us.

Or will it?

Luca, this is such a beautiful and deep post. The crucial and troubling question I take away from it is, can art be the starting point? Can we, by refocusing on art, pull ourselves out of the current slide into ugly and demeaning thoughtlessness? Or does your point that "survival, thriving, and the artistic creation are inseparable" mean that without a threat (real and present, not distant and imagined) to our survival we won't be able to rebuild healthy societies?