After a few weeks of commotion—filled with absurd proposals for a EU army that might have emerged in fifteen years (by which time, Trump would likely no longer be the US President)—there was finally clarity.

Last Tuesday, Ursula von der Leyen presented a new EU initiative: ReArm Europe (I am so tired of the fashion of randomly capitalising letters in the middle of words, which in this case is also meaningless). The EUR 800bn plan is articulated in two phases: the first allows for national investments in defence within the Stability and Growth Pact; the second provides loans and grants to member states for rearmament (or ‘ReArmament’) through the EU budget, the Savings and Investment Union, and the European Investment Bank.

“We are living in the most momentous and dangerous of times. I do not need to describe the grave nature of the threats that we face. Or the devastating consequences that we will have to endure if those threats would come to pass.”

Extract from the Ursula von der Leyen press conference on March 4, 2025.

In the first half of the speech, Von Der Leyen went to great lengths to describe the dangers facing Europe and made a concerted effort not to mention Russia. But on the following day, Emmanuel Macron was less cautious and launched into an all-in tirade against the Russian President.

“Russia has become, today and for a long time, a threat to France and to Europe.” Emmanuel Macron, March 5, 2025.

A discussion involving historical comparisons ensued—Putin reminded Macron that Napoleon met with a poor fate, to which Macron retorted that if there were an “imperialist” in the world today, it would certainly be Putin.

Now, I am certainly not suggesting that Putin is not an unreliable leader with a nasty habit of invading sovereign countries and claiming territory within them. However, reflecting on the past few days, I recall a sentence I heard during a conference: “If there is no enemy within, the enemy outside can do you no harm.”

A deplorable characteristic of Europeans is that we remain convinced – against all indications – that Europe is the best place. Behind a constant veil of minor complaints – too much traffic, delayed trains, dirty streets, sluggish bureaucracy – there lies a fundamental pride. We have the best culture, the earliest civilisations, the longest history, the largest economic market, the highest morals, the deepest ethics, and so on. All these beliefs are arguable or plainly wrong, of course, but they are endearing and deeply rooted, and they inevitably skew our critical spirit: when something truly wrong happens, we always look outside.

But there is little doubt that Europe is profoundly unwell, with unaddressed and unresolved tensions bubbling beneath the surface in society (the migrant issue, of course, demographic decline, identity clashes) and the economy (energy dependence, the decline of manufacturing, and a technological and innovation lag).

However, it is the tensions in a third area that concern me the most, particularly considering the substantial military investment desired by nearly everyone here.

You see, European politics is really not faring well. What is particularly concerning is the momentous rise of populism on mostly the right end of the political spectrum.

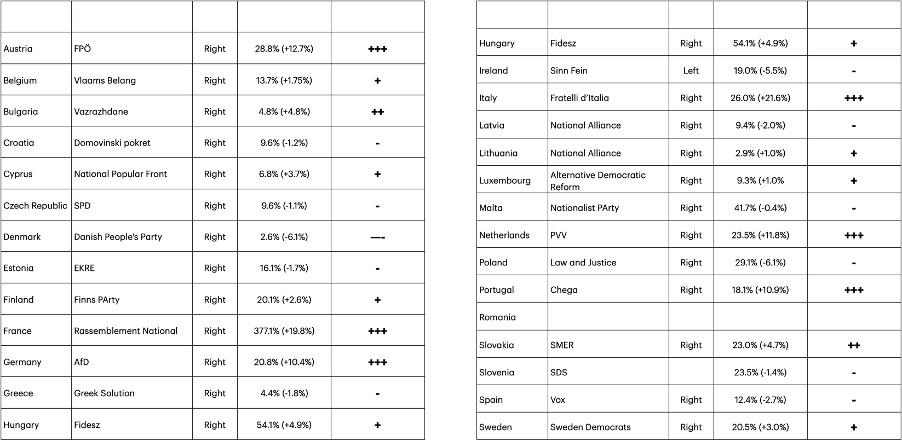

In the table above, I report the scores achieved by the most populist party for each EU member in the last national legislative elections. Not only does the far-right appear to be on the rise, but in the three largest countries of the Union – Germany, France, and Italy – it is experiencing a stellar increase in consensus, ranking second, first, and first respectively. One in six registered voters in Germany chose AfD, one in four voted for the French Rassemblement National, and one in five chose Fratelli d’Italia.

I remember the first day I arrived in Berlin, searching for an apartment on 2nd May 2015. Seventy years earlier on that day, World War II had ended. It was an exceptionally hot day, and in the non-air-conditioned room of my hotel, I watched the news on ZDF, the national channel. I noticed that for the first ten minutes of the programme, the anchor kept his gaze lowered, his head slightly bent, and never looked directly at the camera. When I met some friends a few hours later, they explained to me that this was intended as a sign of deep agony and an apology for the horrific war crimes Germany had committed.

Fast forward ten years, ten million Germans chose to vote for a party that stops just short of declaring itself neo-Nazi (by the way, AfD expelled two of its members for neo-Nazi remarks in 2024 – Maximilian Krah and Matthias Helferich – only to reinstate them a few days after the 2025 election triumph).

In France, Rassemblement National was the leading party in the last three European elections and the most recent legislative elections. Marine Le Pen was the second most voted candidate in the past two presidential elections. Her party was kept from the driving seat by a two-round election system and the ‘Front Républicain’ invoked by its opponents to prevent the far-right from gaining power.

In Italy, Fratelli d’Italia currently leads the Italian government through a centre-right coalition with Lega and Forza Italia. The majority of extreme electoral promises have, thus far, been kept at bay by the presence of Forza Italia in the government.

So, when Macron – who is governing France by the thinnest of margins – says that he extends France's ‘nuclear umbrella’ to all of Europe, should we feel reAssured? When Germany – a country still bound by the Two Plus Four Agreement, which limits its military size (no more than 370,000 troops) and prohibits possessing nuclear, biological, or chemical weapons – promises to do “whatever it takes” regarding defence, should we feel reAssured? When Rheinmetall – which, during World War II, was integrated into the state-owned company Reichswerke and produced 95% of the weapons used by Hitler’s forces – plans to convert two civilian plants, in Berlin and Neuss, to armament production, should we feel reAssured?

For the typically slow and veto-prone European Union to swiftly reach an agreement on spending EUR 800 billion for ReArm is noteworthy. But if the enemy lies within, is the more immediate threat Vladimir Putin sipping a Kir Royale in the Throne Room of Versailles, or a vile and villainous inside hand that, one not-so-distant day, may find itself in control of EUR 800 billion worth of brand-new weaponry?

The cracks on the inside are usually what bring the walls down.

Excellent post, Luca, and I completely agree. I'd like to point out one thing, and to do so I will step gingerly on the mineField. Europeans in general have fundamental pride in Europe, as you note. But European policymakers have often been too willing to mute, censor and even condemn European history and heritage in the name of a multiCulturalism that Europe is not equipped to sustain. This has contributed enormously to the success of the extreme right, in my view. Meanwhile, EU policymakers take pride in identifying Europe with rather abstract universal and globalist values that are good mostly for grandstanding speeches. Add a stagnating economy, and you have a recipe for disaster.