As with economics, India’s growing political relevance could lead to divergent outcomes. In one scenario, India’s current strategy—balancing between the U.S. and China—could succeed and bolster its political influence. On the other, it is a tale of global catastrophy.

I've long lamented the decline of diplomacy, and I’m not alone; this article tackles this issue admirably. But I am too pessimistic, perhaps, and diplomacy is not dead. Defined as a fine balance—walking on a tightrope, balancing (or cancelling out) currents from the left and right, from up and down—we can see it at work in the current political economy of India.

For how long will diplomacy be able to maintain India’s multi-alignment?

In the previous post, I mentioned how India's remarkable infrastructure progress signals the potential for a sweeping wave of industrialisation in the coming years. This advancement would position India prominently among the so-called ‘middle powers’—I would argue it stands as the foremost among them. Strategically, these countries embrace a ‘multi-aligned’ stance, refraining from exclusive allegiance to the U.S. or China. Instead, they selectively engage with both, leveraging economic and political opportunities in a pragmatic balance.

The existence of these middle powers—among them Brazil, South Africa, Mexico, Germany, France, Vietnam, and Australia—undermines the traditional U.S.-China bipolarity. Both superpowers must tolerate this multi-alignment, as each middle power’s unique advantages are too valuable to disregard.

Politically, India appears increasingly aligned with the West—a notable shift given that, during the 1971 Indo-Pakistani War, the U.S. actively supported Pakistan against India. Recently, India signed a Security of Supply Arrangement (SOSA) and a Memorandum of Agreement on the Assignment of Liaison Officers with the United States. Through the (non-binding) SOSA, both countries agree to provide each other priority access to goods and services essential for national defence. This marks a significant escalation in U.S.-India relations, with both nations cautiously eyeing a potentially more assertive China in the region.

Economically, however, India pragmatically leans Eastward. India relies heavily on Russia for critical defence and energy supplies, and it quickly secured Russian oil that Western countries have boycotted since the invasion of Ukraine, undercutting the impact of Western sanctions. Meanwhile, China remains an indispensable trade partner, serving as India’s largest source of imports and its sixth-largest export market.

For how long will diplomacy be able to maintain India’s multi-alignment?

There are certainly sound reasons why the status-quo might hold for some time. The U.S. and the West are eager for a strategic ally in a region slipping from their influence – the Middle East and South Asia. This is important enough to continue to close an eye on India undercutting Western sanctions against Russia. Russia depends on oil revenues from a rapidly developing, energy-hungry India, as long as Western sanctions persist. Meanwhile, China benefits from projecting a 'friendly' stance towards India, presenting BRICS as the basis for developing credible alternatives to U.S.-led institutions such as the IMF, World Bank, SWIFT network, and U.S. dollar-dominated trade.

Currently, no major player seems rushed to disrupt the status quo. But for how long?

This balance is more precarious than it appears. Several plausible scenarios could make India’s multi-alignment untenable, some of which could have catastrophic global ramifications. While many consider the Taiwan Strait or the long-standing enmity between the two Koreas potential flashpoints for global war, a conflict centred on India is, in my opinion, at least as likely.

Some Geographic unfortunate truths

To start, consider India’s geographical position: effectively encircled by both historical and emerging adversaries.

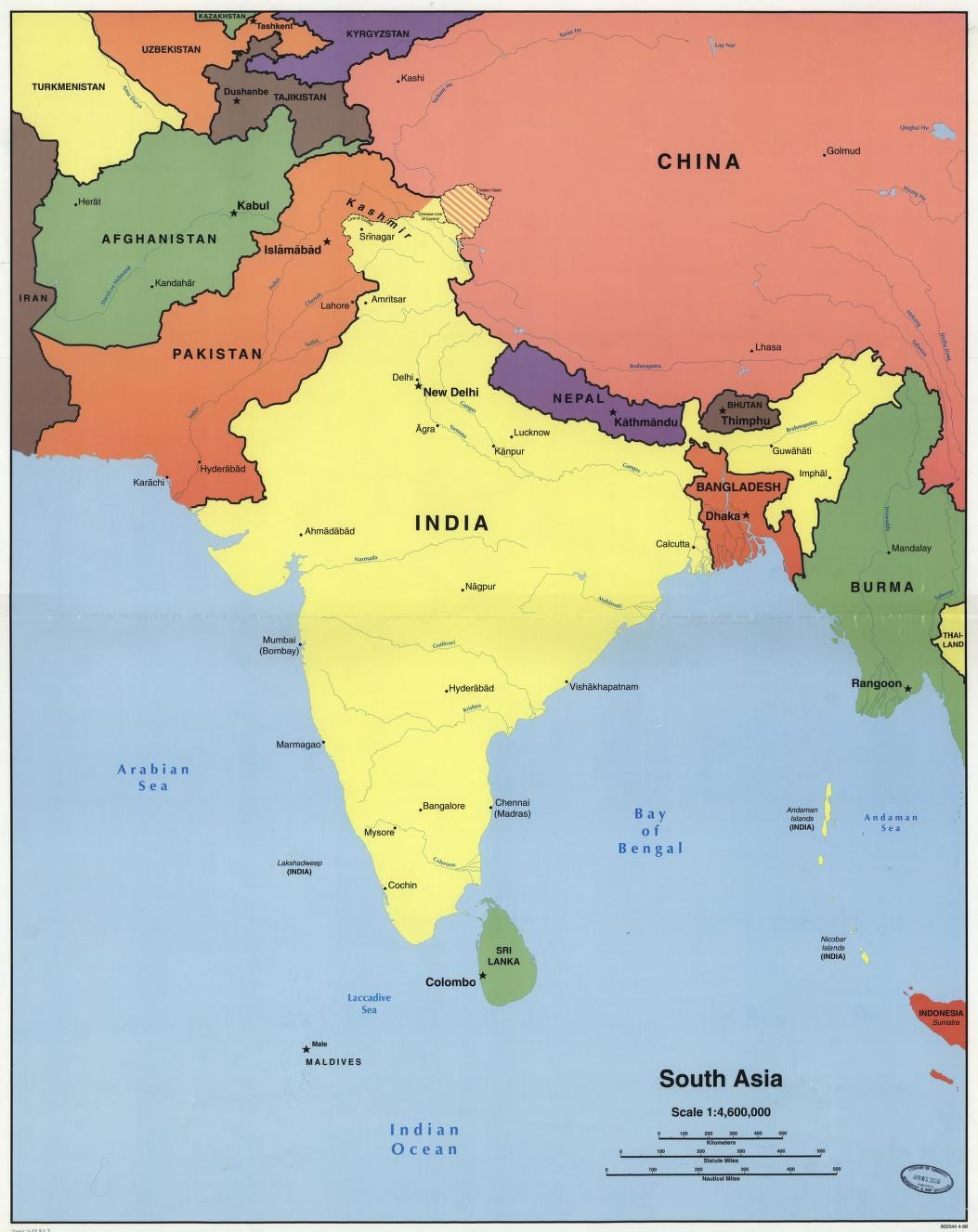

To India’s west lies Pakistan, its historical arch-rival. Once unified under British rule, India and Pakistan became separate nations in 1947 when the British partitioned the territory into the Union of India and the Dominion of Pakistan. This partition later evolved, further dividing Pakistan into the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and now Bangladesh (1971).

Today, the 3,300-kilometer international border between India and Pakistan separates India’s states from Pakistan’s four provinces. The Wagha Border, between the Indian state of Punjab and the Punjab province in Pakistan; the Zero Point, between India's Gujarat/Rajasthan and Pakistan's Sindh. And finally, the Line of Control (LoC), which separates India’s regions of Jammu and Kashmir from Azad Kashmir of Pakistan.

India and Pakistan have fought two major wars (in 1965 and 1971) and faced the 1999 Kargil crisis, a serious conflict that nearly escalated to nuclear confrontation. Tensions have remained high ever since, with the current Modi administration placing anti-Pakistan rhetoric near the core of its political agenda, further intensifying the longstanding hostility between the two neighbours.

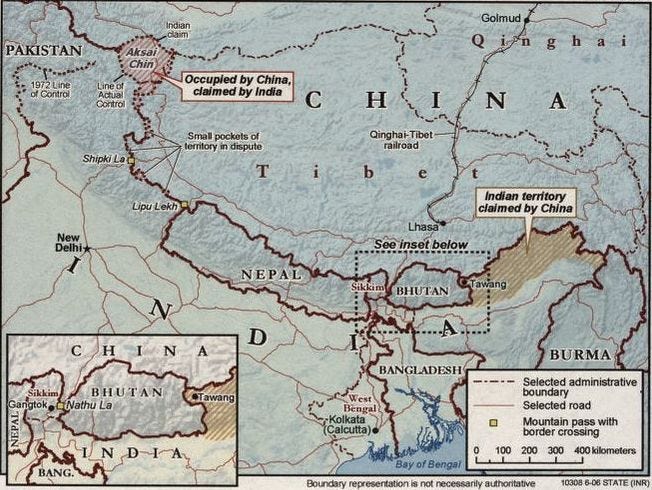

To the north and northeast, India faces China, with two contentious borders: Aksai Chin in the west (administered by China but claimed by India) and Arunachal Pradesh in the east (administered by India but claimed by China). These disputed territories were flashpoints in several confrontations. In the 1962 Sino-Indian War erupted after China constructed a highway through Aksai Chin, linking Tibet to Xinjiang. Chinese leaders, assuming the U.S. would be too preoccupied with the Cuban Missile Crisis to intervene, sought to consolidate control. However, the U.S. responded with aerial support, prompting China to declare a unilateral ceasefire and retreat from most of the occupied territory. Yet, China maintained control over approximately 14,700 square miles (38,000 square kilometres) of Aksai Chin, an unresolved point of contention that continues to fuel friction between the two nations.

Following the 1962 war, India and China established a Line of Actual Control (LAC), which eventually came to signify the entire de facto border between the two nations. Since then, the LAC has been a recurring flashpoint, with skirmishes occurring in 1987, 2013, and 2017 and more significant incidents in 2020 and 2022—though none escalated into full-scale war.

Just last week, the 2020 standoff was officially “closed” through an agreement on patrolling protocols and de-escalation, reached only hours before Xi Jinping and Narendra Modi met at the BRICS summit in Russia. Yet, as the ink dries, many analysts express scepticism that the agreement represents a lasting solution. They argue that, while promising, it lacks the depth to ensure enduring peace between India and China along this volatile border.

To the east lies Bangladesh, a relatively new addition to India’s list of bordering countries with strained relations. Formed in the aftermath of the 1971 Indo-Pakistani War, Bangladesh had until recently maintained robust political and commercial ties with India. However, relations have cooled following the fall of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, who governed for over 15 years and fled to India in exile after ordering a violent crackdown on a student protest last August. A provisional government led by Nobel laureate Mohammad Yunus is steering the country toward elections expected in 2025.

The Bangladesh National Party (BNP), historically adversarial towards India, is seen as the frontrunner, likely to gain a majority and a mandate to govern. During its last tenure (2001–06), Bangladesh saw a surge in Islamic militancy and became a haven for insurgents from India’s Northeastern region. Several terrorist organisations with anti-India agendas took root, with links to prominent BNP figures such as Tarek Zia and Lutfozzaman Babar.

This long-standing animosity between the BNP and New Delhi has fostered a mistrust climate, which could further disadvantage India’s strategic and geopolitical interests if the BNP gains power again.

The Hindus-Sunni Muslims divide

In the event of conflict, India’s current diplomatic strengths could swiftly transform into dangerous vulnerabilities.

Given this backdrop, religion emerges as a potent source of potential conflict.

India is home to two hundred million Muslims, predominantly Sunni. Despite protection enshrined in the Indian constitution, the Muslim population faces increasing discrimination. The Modi administration supports the marginalisation of the Muslim community. His party, the Bharatiya Janata Party – which was founded in 1980 from the political wing of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a Hindu nationalist paramilitary volunteer group – has pursued an aggressive ethnic agenda since it came to power in 2014.

One of the peaks of this agenda was the 2019 Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), which fast-tracks Indian citizenship for Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi, and Christian migrants from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan. The law excluded Muslims and, for that reason, has been criticised as discriminatory and anti-constitutional. Another element of Modi’s anti-muslim policy is the Jammu & Kashmir Reorganisation Act.

Internationally, the ethnic discrimination faced by Indian Muslims has attracted surprisingly muted responses. Europe, while vocal on issues like the Uyghur crisis in China, has largely refrained from addressing the treatment of Muslims in India. In the United States, despite the Commission on International Religious Freedom designating India as a "country of particular concern" in 2020, the Trump and Biden administrations have maintained warm relations with India and rarely raised the issue officially.

Pakistan has also been restrained in its criticism of India’s anti-Muslim policies. For now, India’s domestic stance on its Muslim population has not provoked the strong international backlash that similar issues have elsewhere, leaving it largely unchecked on the global stage.

This might change as the disenfranchisement of Indian Muslims accelerates. A potential catalyst for international attention could be the effective implementation of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) in May 2024, six years after its initial promulgation. CAA only provides a pathway to citizenship for non-Muslim immigrants. Combined with the National Register of Citizenship (NRC)—which the ruling BJP plans to implement nationwide—the CAA could trigger a severe humanitarian crisis. Millions of Muslims excluded from the NRC would effectively lose Indian citizenship and face deportation.

Such a mass disenfranchisement would be a crucial test of regional stability. Pakistan and Bangladesh—particularly if governed by the BNP—would likely voice strong opposition. This backlash could quickly escalate into a broader conflict in the current volatile global climate.

In the event of conflict, India’s current diplomatic strengths could swiftly transform into dangerous vulnerabilities. While advantageous in peacetime, India’s cautious alignment with the West may leave allies hesitant to offer strong support if tensions escalate.

India’s rapidly growing economy, increasingly perceived as a challenger to China’s regional dominance, could prompt China to strengthen its strategic alliance with Pakistan, potentially providing military aid.

If India were to face an attack, its energy demands would skyrocket. Russia, India’s primary oil and coal supplier, might exploit this dependency by raising prices or restricting supply, inadvertently supporting a China-Pakistan coalition. Seeking alternatives, India might look to Saudi Arabia, but Riyadh’s deep ties with Pakistan, Bangladesh, and India’s Sunni Muslim minority would complicate any quick response.

This could leave India encircled, confronting a four-sided war: Pakistan to the west, China to the north, Bangladesh to the east, and Russia as an indirect adversary from the north—with no clear regional allies.

This situation would mark an unprecedented confrontation among four nuclear-armed states. In a worst-case scenario, lukewarm Western support could worsen India’s situation, potentially leaving it no option but to consider nuclear responses. What unfolds then lies between two extremes:

1) A short, limited tactical nuclear exchange would inflict catastrophic damage across parts of Pakistan and India, delivering a grim reminder of the unacceptable devastation such weaponry imposes on humanity.

2) An uncontrollable nuclear World War III, which could spiral into the near-total devastation of life on Earth.

In a harmonious world, India’s skilful diplomacy would serve as a case study for political science students, celebrated for its nuanced balancing of relations amidst complex global dynamics. However, in the current geopolitical climate—characterised by shifting alliances and regional conflicts—maintaining this intricate balance is fraught with far greater risks. Although a catastrophic unravelling of India's diplomatic stance is relatively unlikely, the potential consequences of such a breakdown should not be overlooked. While a formidable asset, India’s growing economic and political clout could also introduce vulnerabilities if this balance is disrupted. These risks warrant careful consideration and strategic hedging for investment decisions that aim to capitalise on India’s growth.

Parts 3 to 5 of the current series will take India’s economic and political situation as the starting point of a scenario analysis. Stay tuned.